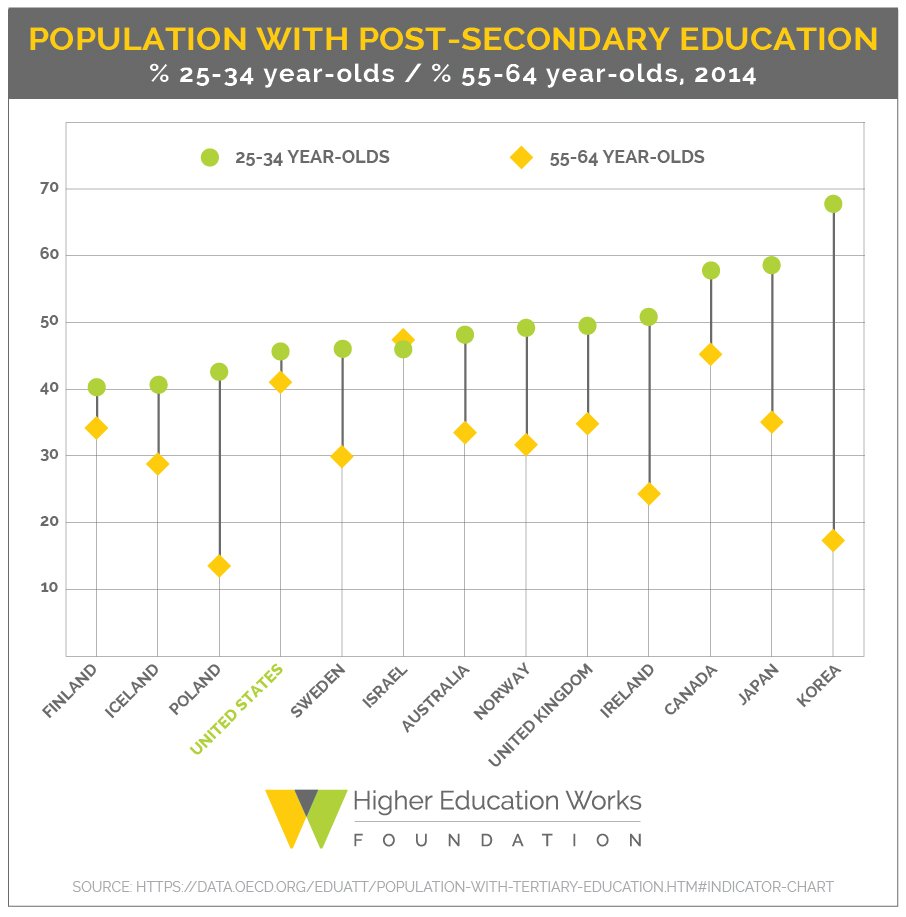

Across the world, countries from Norway to Japan have been making generational leaps in college completion.

In Ireland, barely 24% in the 55-64 age group have earned a degree after high school. Yet nearly 51% of those 25-34 have a degree.

In South Korea, progress has been even more remarkable. Just 17% of the older generation earned post-secondary degrees, but almost 68% of the younger generation have reached that milestone.1

Those investments in higher education have paid huge dividends for national economies, helping lift millions out of poverty and make once-lagging countries into highly competitive global players.

Unfortunately, while much of the world has been making great strides in helping more citizens obtain higher education, the United States has stagnated.

After pioneering mass education in the 20th century, America’s march of generational achievement has almost stalled. Forty-one percent of Americans 55-64 earned a postsecondary degree. A generation later, that figure barely grew, inching up to 45.7% of Americans aged 25-34.

“We remained so far ahead of our competitors for so long … that we began to take our postsecondary superiority for granted,” said a 2006 report from the U.S. Department of Education, better known as the Spellings Commission. “We may still have more than our share of the world’s best universities. But a lot of other countries have followed our lead, and they are now educating more of their citizens to more advanced levels than we are.”2

That report was overseen by then-Secretary of Education Margaret Spellings, now President of the University of North Carolina System. Spellings’ prescient warning about the need for greater investment in college access and attainment has only become more critical in the past 10 years.

In the aftermath of the Great Recession, the vast majority of states reduced funding per student in higher education. That, in turn, raised costs for students and made it harder for more Americans to earn a degree.

“Educational appropriations per student remain 15.3 percent below the 2008 pre-recession high,” according to a report this year by the State Higher Education Executive Officers Association (SHEEO).

Since public institutions serve most students, that shrinkage in state support has profound consequences for educational achievement.

“The educational and economic edge the United States once enjoyed in comparison to other nations has been eroding,” the SHEEO report concluded. “Sound judgment about priorities and extra measures of commitment and creativity are needed in order to regain our educational and economic momentum.”3

The stakes of regaining that momentum are high, both for individual students and the U.S. economy. Rising college costs have hit lower- and middle-income students particularly hard, worsening concerns about social mobility and inequality.

Harvard economists Claudia Goldin and Lawrence Katz found that the slowing in college attainment has driven up the wages of college graduates over their high-school educated peers – simply put, demand for college graduates has grown as the supply has lagged.

“The virtues of education once served us well,” Goldin and Katz conclude in their book The Race Between Education and Technology. “America educated its masses, grew economically, and reduced inequality.”4

Those achievements call for an encore, not a retreat, they conclude.

And states that seize that opportunity will find themselves once again gaining in a global competition.

1] https://data.oecd.org/eduatt/population-with-tertiary-education.htm#indicator-chart

2] http://www2.ed.gov/about/bdscomm/list/hiedfuture/index.html?exp=0

3 http://sheeo.org/sites/default/files/project-files/SHEEO_FY15_Report_051816.pdf, p. 56.

4 http://www.hup.harvard.edu/catalog.php?isbn=9780674035300&content=reviews

Leave a Reply